From the archives: Systemic Denials

I really enjoy rewriting. I actually think that's my favorite stage of the writing process, which I know is kind of an unpopular take. But rewriting, when it's going well, is when everything clicks, when you can take the time to think about the specific phrasing of a sentence or the missing piece of your argument. Though I actually don't rewrite almost anything on this blog on purpose, because I want it to be a more casual and pressure-free writing space.

The first draft is like creating a puzzle, but the pieces are all scattered in the box. Rewriting is when you get to sit down at the coffee table and put on some cozy music and try out different pieces to see how they fit together to create an actual image.

I'm going to revise/rewrite a paper I wrote it the summer going into my senior year at USC for the class ENGL 352. The class was on revolutionary history, literature, and politics of France and the United Kingdom.

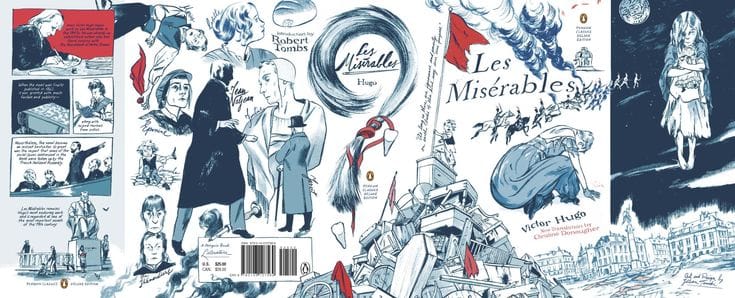

The paper is on Les Miserables, by Victor Hugo. I wish I remember what the prompt was. Probably something on Victor Hugo's political ideology.

My writing professors in both the cinema and English departments wouldn't let us forget that mantra "writing is rewriting," and I usually got the chance to revise and resubmit my work at some point during the semester. But since this class had less of an explicit writing emphasis, and the curriculum was really packed, I didn't ever revise this one.

I was quite proud of this paper. I wrote it in one sitting the day of the deadline. I usually don't like to put things off until the last minute, but the turnaround for that class was really fast and I felt really rushed. Like most papers, I developed my ideas as I wrote it, and it was only at the end when it was 11:57 two minutes before the deadline that I had a clear sense of what my argument actually was.

I have previously wanted to publish some of my college work on here. But I don't really want to just publish them on their own anymore. Instead, I thought it would be fun to publish this paper on its own and then republish a revised version.

If I enjoy doing it with this, I'll do the same with some others. At some point, I'll post the revision along with a summary of what I changed and why.

I really like the ideas in this paper. I just think that my thesis needs to be revised, and the arguments derived from that thesis need to be more concise and streamlined throughout. Organization could also use some work. You'll also notice that there are a lot of repeating phrases, clunky sentences, and duplicate arguments in here. And some generally sloppy sentences. This is a byproduct of me writing this in one sitting in a rush. If I'm remembering right, there was also a pretty high page count requirement so I think some of the repetition is just me dragging it along to make it longer.

I actually found the notes my professor gave me on this as well! I got an A, he was a generous grader and a very nice guy and good professor.

"A - Good. The first page or so is rather dense, and I found myself having to dig through your arguements— but the paper really gets into its stride and achieves a natural flow + clarity in the midpoint. You have a wonderful natural intelligence, and pull telling details from the text. Well done."

Systemic Denials

In Les Miserables, Victor Hugo primarily shows his progressive views through his recurring study and critique of the criminal justice system. But more specifically, Hugo is profoundly interested in the idea that oppression is systemic in nature. He routinely describes and critiques the criminal justice system in a way that today in modern Western liberal circles would be called something such as mass incarceration or the prison industrial complex. Through the plight of his characters, Hugo illustrates institutional cycles of poverty and incarceration as a moral failure by society that is designed to keep incarcerated people from ever reaching social mobility or personal peace. The tragedy of the criminal justice system, to Hugo, is that he believes that people can achieve personal redemption but systematic oppression stops them from being able to achieve it by keeping them in the same low place. This is why Hugo’s moral messages are also political: he encourages people to reject systemic oppression by evaluating people as human and not as labels designed to keep people stuck in place.

Hugo defines his progressive politics by consistently illustrating that much of the plight of the poor is presentable if social services and reform was provided by the government. Hugo illustrates a vision of what a progressive government could be with his description of Jean Valjean as Monsieur Madeleine’s factory owner and mayoral career in Montreuil-Sur-Mer. He describes a near utopic environment where social problems such as “Unemployment and poverty were unknown.” (Hugo 149). This was created by the implementation of social services by Madeleine such as a hospital and the intentional availability of work to anyone who wanted it. This is a stark contrast of government style to the yellow passport that marked Jean Valjean as a convict and barred him from finding work, leaving crime as his only option. This vision is not based on legal status but personal character. “He [Madeleine] insisted on one thing only: Be an honest man! Be an honest woman!” (Hugo 149). The key to this idealistic vision is the concept of the opportunity for change. The availability of authority providing opportunities created positive change in the village on a personal, economic, and societal level. “Before Pere Madeleine’s arrival the whole place was languishing.” (Hugo, 148) but intervention and the breaking down of conventional systemic barriers to employment created a system that helped impoverished people become productive members of a capitalist society. “According to one English statistic, the primary cause of four out of five thefts in London is hunger.” (Hugo 82) Hugo plainly states. To Hugo, poor people are forced to become poor, then forced to become criminals, and then forced to stay criminals. This is the variable that is completely absent from the criminal justice system that Jean Valjean and others are consistently victimized by. There were no victims of Madeleine’s system described by Hugo. It’s almost as if Hugo implies that if only the larger government acted like this many social injustices would vanish just as quickly. In other words, if larger governments were more progressive and took action to intervene in harmful systems instead of perpetrating them. If governments actively helped people instead of punishing or abandoning them.

Hugo depicts people who are good and sympathetic but caught in cycles of poverty and criminality to create situations of tragic injustice that make systematic harm done by the contemporary criminal justice system a villainous force. Jean Valjean is the primary example of someone forever marked by their “convict” label no matter how good and pure they are. A striking example of how Hugo shows how society feels about Jean Valjean is in the newspaper excerpt announcing the believed death of Jean Valjean after his front as Monsieur Madeleine was uncovered. He is introduced as “A convict” and only in the last sentence is named, “Jean Valjean.” (Hugo 340). No mention of the name Madeleine, which is important because it is the one that Jean Valjean created for himself. The article is a cruel reminder that the only identity that matters in society is the one imposed on someone: a legal name or a legal status, such as “convict.”

It also shows that social mobility in the society Hugo describes is a myth. Valjean did what seems to be impossible in Montreil Sur-Mer, being both a good example of a capitalist citizen with his business success, and an example of near perfect personal virtue for the town such as providing work, kindness such as saving a neighbor from under a mule cart, and creating social services. None of it was enough to save him from being remembered and treated as someone to be scorned and forgotten. As soon as Jean Valjean was labeled a criminal, he had no chance of redemption in the eyes of greater society. Through this situation, Hugo criticizes the impossibility of escaping the criminal justice system. People such as Jean Valjean who have achieved personal redemption are condemned for life by the government and society.

Another example of this is Fantine, an angelic young woman forced into prostitution by poverty and stigma surrounding being an unwed mother. Fantine is very eager to make a living wage to support her daughter, Cosette. However, the fact that she’s a single mother makes the other women in the factory distrust her. She is fired indirectly because of it. Her only option becomes prostitution. She did not choose this criminal life but was denied all other opportunities. She is politically aware of this system to an extent, “I had my little Cosette, I was forced to become a bad woman.” (Hugo 179) she laments to Javert, a police officer who arrests her for hitting a “gentleman” attacker. Her phrasing of being “forced” towards criminality suggests she is trying to explain to Javert and the reader that becoming a criminal was not because of personal vices or desires but an inability to survive on anything else. But once she enters the criminal justice system by being labeled a criminal/prostitute, much like Jean Valjean, she is only seen as one without any context even though she often tries to give it. Javert describes Fantine as “The wretch” twice instead of her name while naming her attacker “Monsieur Bamatabois” the first time because he is of a perceived greater respectability, an “enfranchised owner” of real estate (Hugo 181).

Hugo even names one of his chapters “Systematic Denials” (Hugo 247) during a sham trial where an innocent man, Champmathiew, is nearly convicted as Jean Valjean. Here is another character who seems somewhat aware that the rules of the establishment are set up against them. Champmathieu, who is poor and uneducated, is unable to answer the court’s questions eloquently. Although “stupid and bewildered” (Hugo 243), he has a moment of insightful defense of himself. “‘Go on, answer!’ I’m no good with words, I didn’t go to school, I’m a poor man. That’s where people are making a mistake, in not understanding that.” (Hugo 250) says Champmathieu. He is not able to defend himself in court because of a systematic lack of opportunity in that there were no social services, such as schools, available to educate him or lawyers provide to properly defend him. The “mistake” he references is the court’s inability or unwillingness to consider those factors. The dramatic irony of the readers knowing the stories of sympathetic or pure hearted individuals such as Fantine, Jean Valjean, or Champmathiew, and then seeing them punished by the justice system as if they were villains, is where much of the tragedy of Les Miserables comes from. They want to be law-abiding citizens and for the most part they are, but because they are perceived as criminals, they are prevented from ever achieving personal or economic growth. Fantine wants to be a mother and does not want to be promiscuous, but all of her vices are due to economic cycles of poverty and then the inescapability of being labeled a prostitute. Hugo suggests that people want to be good but once labeled “bad”, have no choice but to become bad.

Hugo offers some guidance to readers of how to reject political and economic systems that dehumanize people. This is by regarding others by character and not as labels. There are moments of personal revelation and transformation from bitterness to kindness that are triggered by simple acts of kindness and humanity towards people who have never received it before. The first is Jean Valjean’s. The Bishop forgives him for stealing his silverware and candlesticks. As a result, Jean Valjean transforms. First he believes “life is a war” (Hugo 84) and “Never since childhood, since his mother, his sister, had he ever encountered a friendly word, a look of kindness” (Hugo 84). The simple act of forgiveness prevents him from committing other crimes entirely; he is “no longer capable-” (Hugo 105) of stealing from a child through his newfound humanity. The cycle of criminality is not broken by years in prison but by a simple gesture. Jean Valjean carries on the favor by sheltering and protecting Fantine after her arrest. Hugo describes Fantine’s thoughts as “... she felt the dissolution and dispersal inside her of the frightful shades of hatred, and the birth in her heart of something beyond an expression, and indefinable warmth that was joy, trust, love” (Hugo 182). This is again, the dissolving of a cycle. With his support, support that was not given by the government, she stops being a prostitute shortly before her death. This is not political upheaval or a policy change, this is simple kindness. Although he discusses political revolution and change in other sections he also uses these examples to emphasize the power of everyday interactions to act as forms of political resistance and social remedies. A prostitute and a thief were taken off the streets and became respectable citizens not through punishment and stigma but through personal forgiveness and kindness. They were both able to achieve a level of personal redemption and transformation that was only harmed by the criminal justice system. At the end of the novel, Marius archives personal moral redemption by forgiving Jean Valjean for his criminal past and embracing him as an “angel” (Hugo 1296) because of his personal character. Again, and again, Hugo emphasizes that most people labeled as villains are criminals do not want to be villains and criminals but are forced to become so. He criticizes these systems of poverty and incarceration on a political level but also shows how meaningful personal relationships and compassion works to render these oppressive systems weak.